REVIEW: Why Dáil Committee Rejected Assisted Suicide

THANK YOU: DÁIL COMMITTEE REJECTS ASSISTED SUICIDE BILL.

This week, we joined with doctors, disability rights activists, and many others, to welcome the good news that the Oireachtas Justice Committee has comprehensively rejected the bill which sought to legalise Assisted Suicide in Ireland. It is a significant achievement for everyone who worked to protect the most vulnerable from the devastating effects of Assisted Suicde.

Noting the widespread opposition from across the spectrum to the proposal, including from a significant majority of medical practitioners, the Committee also drew attention to submissions from Life Institute supporters, whose quality and number merited a separate summary in the report.

The Committee drew attention to our contention that Assisted Suicide was increasingly being seen globally as a means to cutting healthcare costs – and noted that we quoted a recent paper published in The Canadian Medical Association Journal, which claimed that millions of dollars could be saved in health care spending by ‘assisting’ people to die. Similarly, a Canadian budget report allegedly stated that $149 million could be "saved" on the annual cost of end-of-life care by utilising assisted suicide.

We would like to extend our special thanks to you for your considerable effort in making a submission to the Committee, and for the part you played in ensuring the rejection of the Assisted Suicide Bill.

Your support for Life Institute’s initiative, the Don’t Assist Suicide campaign, has also helped us to reach almost a million people with powerful, factual messaging on this issue.

Our campaign has brought to the fore the incontrovertible facts regarding the dangers of Assisted Suicide, and highlighted the danger of devaluing the lives of the elderly, the sick, those with a disability, and those vulnerable to suicide.

Huge credit is due to the medical bodies and professionals who have been almost unanimous in their opposition to this bill, and to all those brave souls who have so courageously shared their personal stories to urge for better and improved care instead of Assisted Suicide.

It is important to remember that over 2500 healthcare professionals signed a public letter rejecting the Bill, and that a wide range of leading medical professional representative bodies and associations also strongly opposed the measure.

The issue is now being sent to another Special Committee to review and examine the whole area of Assisted Suicide, but it looks certain that the current bill, proposed by Gino Kenny TD, will not be supported by the Dáil.

In this review of the Committee’s report, we look at the evidence proffered in submissions made in the separate categories, and suggest what actions are now required.

PURPOSE OF THE COMMITTEE’S REPORT

The Joint Committee on Justice was tasked with scrutinising the so-called Dying with Dignity Bill which has been proposed by Gino Kenny TD and which sought to legalise Assisted Suicide in Ireland.

The bill proposed to make it legal to allow a doctor to “enable” a patient end their own life, if a terminal illness was diagnosed.

As we pointed out in our submission:

1. Despite media claims, relief of pain and suffering is not mentioned in the Bill

Although media reports around the Bill frequently repeat the campaigning argument that the measure will only seek to help those who are experiencing “unbearable suffering”, the Bill contains no such requirement as a grounds for Assisted Suicide. There is no requirement that the person who seeks a doctor to end their life is experiencing unbearable pain or suffering, as is often claimed. It’s simply not in the text of the proposed legislation.

Inexplicably, Deputy Kenny, in a September 2020 discussion on Newstalk did not seem to be aware of the contents of his own bill, insisting that his proposal provides Assisted Suicide as a relief for “unbearable suffering”, when it does no such thing. It is to be assumed that the Justice Committee is more familiar with the Bill than its originator.

2. The term "terminally ill" is wide open, with no requirement to be at end of life

The Bill requires that a person be ‘terminally ill’ to avail of assisted suicide. A terminally ill person is defined as “having an incurable and progressive illness which cannot be reversed by treatment, and the person is likely to die as a result of that illness or complications”. This broad definition could include Parkinson ’s disease, heart disease, dementia and many other conditions.

As the Committee will be aware, people suffering from incurable and progressive diseases can live for many years. Yet, there is no requirement that the person be at the end of life to seek assisted suicide - once a diagnosis is received, the ending of one's life can be requested.

3. The Bill ignores the evidence that vulnerable people will be pressured to end their lives

The Bill makes almost no effort to include safeguards for vulnerable people. It is now well established from the experience of other countries that vulnerable people feel under pressure to die by Assisted Suicide. Some 56% of people who died by assisted suicide said that being a burden on family, friends and caregivers was a reason to end their lives, according to a 2017 study in Washington State.

4. Conscience rights are not protected - doctors would be obliged to refer patients for assisted suicide, striking down their right to conscientious objection.

Despite these very obvious and dangerous flaws, a majority of TDs had actually voted in favour of progressing the Bill to the Justice Committee stage, where it was rightly rejected. It can only be assumed that these TDs were either careless in their reading of the Bill or careless as to the obvious dangers it contained.

THE COMMITTEE’S FINDINGS – RECOMMENDATION TO THE DÁIL

The Committee wrote:

“Based on its consideration, the Select Committee determined that the Bill has serious technical issues in several sections, that it may have unintended policy consequences (particularly regarding the lack of sufficient safeguards to protect against undue pressure being put on vulnerable people to avail of assisted dying), that the drafting of several sections of the Bill contain serious flaws that could potentially render them vulnerable to challenge before the courts, and that the gravity of such a topic as assisted dying warrants a more thorough examination which could potentially benefit from detailed consideration by a Special Oireachtas Committee.

“However, this should be undertaken at the earliest opportunity with a set timeframe within which the Special Committee must report.”

“Therefore, the Select Committee recommends that the Dying with Dignity Bill 2020 should not proceed to Committee stage but that a Special Oireachtas Committee should be established, at the earliest convenience, to undertake an examination on the topics raised within and which should report within a specified timeframe. In addition, all submissions received by the Justice Committee would be shared with any such Committee.”

In short, the Committee did not recommend that the Bill should proceed any further or be voted into law by the Dáil. They also decided AGAINST referring the issue to a Citizen’s Assembly.

The Committee said it had considered:

Arguments AGAINST progressing the Bill (for rejection)

• The Bill in its current form was simply unworkable, particularly where fundamental elements of the Bill surrounding safeguards were identified as problematic;

• The legal analysis demonstrated that this Bill was not fit for purpose and that new legislation would need to be designed if this topic were to be progressed further through the legislative process;

• It would not be appropriate for the Committee to continue further examination of a Bill or to recommend that it progressed in view of the serious flaws identified and where sections of it may be vulnerable to constitutional challenge;

• The Committee was conscious that the topic contained in the Bill was of such gravity it would benefit from the attention of a standalone Committee to ensure a thorough examination could be undertaken;

• It would not be possible for the Justice Committee to devote significant time to examine a topic of this gravity, nor would it do justice to the topic to have it competing with other items currently on its Work Programme;

• It was argued against proposing that the matter be referred to a Citizen’s Assembly as Members considered that Parliament is the appropriate forum for consideration of this matter;

And also Arguments FOR progressing the Bill (against rejection)

• While the legal advice is sound and must be taken seriously, it does not mean that the Bill cannot be improved and still progress to the next stage;

• The topic deserves to have a sufficient level of scrutiny and debate undertaken and that it was the Members’ responsibility to consider what the best method of undertaking such scrutiny would be;

• Establishing an Oireachtas Special Committee to undertake detailed consideration of the topic was suggested, as this could provide all stakeholders with an opportunity to express their opinions while affording the topic the level of consideration that it merits;

The arguments against the Bill were clearly held to be the more persuasive.

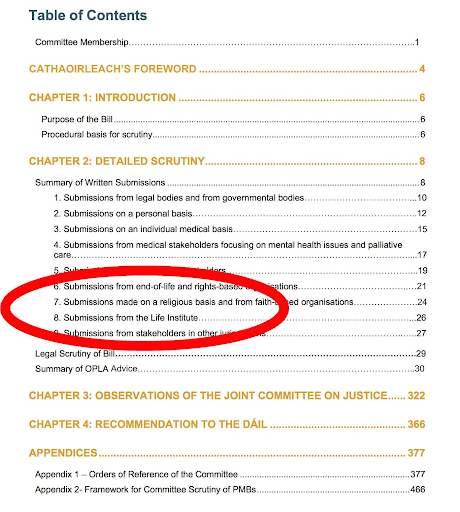

SUBMISSIONS RECEIVED BY THE COMMITTEE

The Justice Committee said it had issued an open call for written submissions on the topic “to increase the participation of civil society and reflect their views on the topic, in so far as possible.

They acknowledged that over 1,400 submissions were received from various stakeholders, on both an individual and organisational level by the deadline on 22nd January 2021 – and they listed those submissions in the following categories.

A SIGNIFICANT MAJORITY OF THE SUBMISSIONS FROM MEDICAL BODIES OPPOSED THE BILL – AS WAS THE CASE IN MOST OTHER CATEGORIES

We will now look at the summary of each of these categories in turn.

MEDICAL SUBMISSIONS

There were two categories of submission on a medical basis: from individuals – and also from medical stakeholders focusing on mental health issues and palliative care

Nearly all the 36 submissions in the latter category stated their opposition or concerns to the proposed Bill while a majority of the 64 individual medical submissions also opposed the proposal.

Several medical professionals objected to the title of the Bill – ‘Dying with Dignity’. They pointed out that it undermines the work of palliative organisations by implying that assisted dying is the better or the only way to have dignity when dying. Thus, they argued that it should be changed to ‘Assisted Dying’ to more accurately reflect the intentions behind the Bill and to represent that palliative care also provides a dignified death.

Many medical stakeholders in this category had experience working in a palliative capacity and believed in the significant benefits of good palliative care and pain management, which they believe provide a sufficient alternative to ease a patient’s suffering from a terminal illness.

These submissions argued that portraying assisted dying as an alternative to suffering, would promote the wrong message in relation to terminal illnesses and that society should place more value on palliative care in general, as individuals may have an inadequate understanding of how palliative medicine can transform the quality of their life.

They also raised the issue of the ongoing underfunding and regional disparity in the provision of palliative care services, and were concerned that assisted dying could be seen as a more ‘cost-effective’ approach to addressing the needs of those facing end-of-life illnesses, and that this would shift the focus away from the development and the delivery of palliative care services and discourage research into palliative care.

Therefore, they argued that investment and expansion of these palliative care services and hospice service should be the priority and focus over legislating for assisted dying.

Research by the Irish Palliative Medicine Consultants’ Association (IPMCA) which had demonstrated that palliative care experts and other members of the medical profession were themselves strongly opposed to the introduction of assisted dying was submitted. A survey undertaken by the IMPCA in 2020 found that 88% of palliative medicine doctors are opposed to assisted suicide.

Some of the submissions highlighted concern that the right to conscientious objection did not seem to include pharmacists, even though they would also play a role in the process of assisted dying similar to other assisting healthcare professionals.

Several submissions also expressed their belief that the current legislation is lacking robust, and carefully monitored safeguards in several areas, despite the critical need for such safeguards.

Medical practitioners also said that adequate consultation of medical, nursing, or allied healthcare personnel on the issue had not yet occurred.

Many also opposed the introduction of this Bill based on the principle that enacting this legislation could begin a ‘slippery slope’ or ‘policy creep’, where robust legislation that seeks to limit the circumstances where assisted dying is allowed could be subject to pressure and that future amendments could change the original Bill significantly and result in the criteria allowing those who can avail of assisted dying to be broadened.

Submissions highlighted the recent governmental decision in the Netherlands (which had previously been approved in Belgium in 2014), which would allow for assisted dying to include children suffering from a terminal illness once they have consent from the child, their parents and doctors involved.

Questions were raised as to how those in charge of making these decisions would determine which lives are proper candidates for termination and ‘where the line would be drawn’.

Additionally, submissions highlighted that introducing legislation on assisted suicide could significantly harm the patient-doctor relationship and could undermine the trust between the public and the medical profession.

They argued that the deliberate ending of a patient’s life goes against core medical ethics and would breach the fundamental principle of ‘do no harm’ that lies at the heart of the doctor-patient relationship. Some medical practitioners highlighted that patients of theirs have asked to speed up their deaths and were later happy that they did not do so.

Similarly, submissions raised the point that it can be very difficult for physicians to accurately predict the life expectancy of a terminal disease. The diagnostic uncertainty that surrounds end stage treatment of incurable progressive disease like heart disease and cancer could pose risks by allowing individuals with these diseases to apply for assisted dying on the assumption that their death is impending, when in some cases these individuals may live months or even years longer than predicted.

They believe that the Bill also fails to set requirements regarding the professional assessing capacity of doctors when deciding what counts as a terminal illness, stating that mutual agreement on this between clinicians is poor in general.

Additionally, concern was expressed that the Bill contains no requirement for psychiatric assessment of the patient to ensure that they are providing informed and valid consent for this procedure and similarly, a submission in another category highlighted the lack of psychiatric assessment to recommend treatments for patients who may develop depression or suicidal intentions after being diagnosed with a terminal illness.

A few submissions in this category, however, highlighted their support for the Bill, arguing that it would provide a more dignified end to those who have been diagnosed with terminal illnesses by allowing them autonomy over their lives in selecting when to end their suffering and preventing their family members further distress by seeing them in unbearable and ongoing pain.

SUBMISSIONS FROM THE LIFE INSTITUTE

“Some 324 submissions were sent in from those affiliated with the Life Institute, an organisation which is pro-life, pro-family and believes in the sanctity of human life,” the Committee noted. “They strongly oppose this Bill.”

“Among the points raised in their submissions, additional to the points raised in other categories include:”

• That assisted suicide is strongly resisted by disability rights groups for the clear impact it would have on devaluing the lives of those with disabilities and the risks it poses to them.

• That the High court case in Marie Fleming v Ireland gave a damning judgement regarding the perceived difficulties of ensuring that safeguards adequately protect the vulnerable members of society under assisted dying legislation, stating that:

“even with the most rigorous systems of legislative checks and safeguards, it would be impossible to ensure that the aged, the disabled, the poor, the unwanted, the rejected, the lonely, the impulsive, the financially compromised and emotionally vulnerable would not avail of this option to avoid a sense of being a burden to their family and society.”

• They claim that increased pressures on national healthcare budgets, which were struggling to provide resources for long term care and global trends towards ageing populations in certain areas of the world create a risk that assisted dying would be used as a solution and a cheaper alternative for end of-life healthcare provision, at the expense of increasing investment in palliative care and other end-of-life services.

They quote a recent paper published in The Canadian Medical Association Journal, which they state claimed that millions of dollars could be saved in health care spending by ‘assisting’ people to die. Similarly, a Canadian budget report allegedly stated that $149 million could be "saved" on the annual cost of end-of-life care by utilising assisted suicide.

FOR MORE ON THIS ISSUE SEE: https://www.facebook.com/lifeinstitute/posts/3972172916155468

SUBMISSIONS FROM END OF LIFE AND RIGHT-BASED ORGANISATIONS

A majority of the 29 submissions received in this category were against the Bill the Committee said.

The arguments from organisations that had concerns with the Bill were that the consultation process should be extended as they did not feel that has been adequate opportunity to consult on the Bill and to allow for a broad, timely and adequate consultation process, particularly with key stakeholders including older people’s councils and national age sector organisations, and stakeholders representing those living with dementia and people with disabilities.

Additionally, pro-life organisations highlighted the ‘burden’ argument and elaborated that pressure on vulnerable people to avail of assisted suicide could take a subtle form. This could occur due to shifting attitudinal perspectives in society that would begin to devalue the lives of vulnerable people after assisted dying was introduced or through the lack of appropriate supports and services, as stakeholders believe that funding towards palliative care may decrease if assisted dying is a cheaper option for end-of-life care. Thus, stakeholders added to views expressed in the medical category who argued that focusing on assisted dying as a solution to better end-of-life care is incorrect and that the focus should be on improving palliative care provision so that access to services is even across every region and that palliative health care assistants receive more support, training and feel less undervalued in their role. They also point out that if carers feel more respected and supported, then those in their care need not feel as much of a burden on them. They believe that society should affirm the dignity of people who are dependent on others for their care and highlight the fact that a natural death can be dignified even if the end of life involves dependence and disability for the individual concerned.

Stakeholders in favour of Assisted Suicide argued that “the reality of palliative care means that while it accommodates the needs of the majority, it cannot prevent all suffering and that it is inhumane to allow people to suffer through unbearable pain.

SUBMISSIONS FROM LEGAL BODIES AND GOVERNMENT BODIES

Of the 8 submissions in this category, while one was strongly opposed and one was strongly in favour, the other submissions did not adopt a stance on the topic.

Some submissions felt that the Bill had been rushed; that media coverage used imprecise terminology, and that fundamental strategies of suicide prevention should not be compromised.

Evidence from other jurisdictions where assisted dying has been permitted should also be considered during the deliberation processes, as these jurisdictions could provide an insight into human rights implications of the Bill and the potentially negative impacts on vulnerable groups in society, were amongst the recommendations.

The critical need for robust safeguards in such legislation was highlighted, and it was noted that the diagnosis of a terminal illness is a peak period of vulnerability.

The risk of this legislation being abused could harm these individuals, who may feel forced to opt for assisted dying and be robbed of many more fulfilling years, was considered.

In terms of assessing an individual’s capacity to make an independent decision to avail of assisted dying under Section 9 of the Bill, it was pointed out that the current Bill does not recommend for a range of practitioners to assess the patient, including a GP that would often have a better knowledge of the person wishing to end their life and thus a better insight into their capacity to make this decision.

Additionally, there are insufficient safeguards or penalties in the Bill to discourage a declaration being witnessed by a beneficiary of the estate who could have pressured the individual to avail of assisted dying, the report said.

SUBMISSIONS MADE ON PERSONAL BASIS

900 submissions were received in this category received. Most of the key points highlighted by the Committee were opposed to Assisted Suicide.

They said: “A point that was repeated frequently throughout submissions in all categories was concern that this Bill could result in abuse of the sick and vulnerable, who may perceive themselves to be a burden on their family and feel pressured into opting for assisted dying”

Being made to feel a burden if they need frequent care, or the danger of pressure and coercion from relatives who are interested in benefiting from their inheritance after they die or from insurance companies, who would no longer be willing to cover the expense of their end-of-life treatments, was also raised frequently

Submissions argued that if enacted, the Bill would devalue the lives of the vulnerable in society, including the elderly, those with mental health or psychiatric issues and those with intellectual and physical disabilities and that the value of a life should not be decided based on what a person can contribute to society.

In some submissions, elderly people expressed their personal dismay, as they felt that after working hard all of their lives, the prospect of this Bill being passed made them feel as if society was demonstrating that they were of little value. They also expressed fear regarding the consequences this Bill would have on them as older people in society and the pressure that might be on them to avail of assisted dying.

Others felt social solidarity would be undermined and the fabric of society destroyed, as assisted suicide may eventually switch from being a ‘choice’ to becoming a social norm or the expected ‘choice’.

In addition, several submissions highlighted that they believed the timing of this Bill was inappropriate, arguing that legislating for assisted dying, at a time when the Government is locking down the country to prevent deaths from Covid-19 seems paradoxical and insensitive.

Others also questioned the conflict between the Bill’s intention to promote assisted suicide as an option and the increased societal focus on mental health and suicide prevention, arguing that the Bill essentially undermines this anti-suicide messaging. They believed that if this Bill were enacted it would normalise suicide and introducing this legislation would send a message that makes suicide more acceptable to society.

Similarly, some submissions claimed that, where assisted suicide had been introduced in other jurisdictions, the rates of suicide in the general population had increased and stated that the Netherlands had seen a rise in the number of suicides by almost 34% in the 10 years after assisted dying was legalised.

Religious motivations were sometimes mentioned as was a further step towards devaluing life.

Many felt "terminally ill" was too broadly defined, with no requirement to be at the end of one’s life, as the current phrasing could include people with disabilities such as Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, dementia and many other conditions that are incurable but are currently viewed as treatable and liveable conditions.

Others expressed support for the Bill, sharing personal stories of their own illnesses or of relatives faced with terminal illnesses, and argued that people should be allowed to have autonomy and choice over their death.

However, others who cared for relatives with terminal illnesses, however, believed that palliative care and hope are the most important approaches to a terminal illness and opposed assisted dying as they believed it did not provide such a caring and community oriented approach. It was also argued that certain people gain immense value and comfort at the opportunity to care for their loved ones during their terminal illness and this can help these people to cope and manage their grief from this experience.

SUBMISSIONS FROM ACADEMIC STAKEHOLDERS

Academic stakeholders were divided on the issue.

In submissions that argued against the Bill, one stakeholder with longstanding experience in palliative care provision said that requests for assisted dying are infrequent and mostly a ‘cry for help’, and that this often diminished when good care was provided.

One stakeholder in favour of assisted death argued that it would regulate a practice that is happening anyway.

SUBMISSIONS MADE FROM FAITH-BASED ORGANISATIONS

Individuals, groups, and organisations who sent submissions to the Committee on a religious basis accounted for approximately 435 submissions and all of these submissions fundamentally opposed this Bill on religious grounds.

Firstly, many of the submissions felt that assisted dying was always morally wrong and they equated assisted dying with murder.

They argued that Irish society is still nominally Christian and needs to reflect on itself and on its core values.

Secondly, these submissions believed in the sanctity of life or that all lives have value, and repeated previous arguments that introducing assisted dying would further devalue human life.

Thirdly, they argued that we have a duty to protect the vulnerable in society, who would face increasing pressure to avail of assisted dying if it were introduced. Some submissions even argued that allowing assisted dying would alter society’s attitudes towards the elderly and vulnerable and create a culture where these groups are not valued and they may begin to think that ‘they’re better off dead’.

Finally, they also believe that assisted dying would be a step back for genuine healthcare and that it is unnecessary as palliative care is a sufficient method of assisting those who are terminally ill.

One submission argued that despite the stated intention of the Bill to be motivated by compassion for the terminally ill, their understand having compassion to mean “suffering with” someone and that assisted dying reflects a failure of compassion on the part of society to respond to the challenges of caring for patients at the end of their lives.

SUBMISSIONS FROM OTHER JURISDICTIONS

Submissions were received from individuals and organisations in other jurisdictions, including some of whom were Irish but lived abroad and wanted to bring the perspective of their jurisdiction into their submissions. Of the 10 submissions received in this category there was an even split between those in favour of legislation on assisted suicide and those against.