Men

How abortion effects men

The mental pain and anguish suffered by post-abortive women is widely known and well documented.

But, what about a man involved in the decision to abort his baby? Does he too suffer negative psychological effects?

Men are often forgotten by abortion advocates and the media, but the truth is that men are often just as devastated by abortion as women.

Some of the negative effects felt by men involved in the abortion process are:

Grief and sadness

Men in our culture may have difficulty articulating a sense of sadness. But, after an abortion, men often find themselves sad and depressed

Masculinity

After abortion, men can feel a sense of being unable to protect his partner or their offspring. This can be incapacitating, affect self-esteem and self-worth, and cause helplessness

Rage or anger

Rage and anger is often how post-abortive men lash out after the abortion loss. Anger may be internalized or targeted toward the mother of the child or other parties involved

Risk taking behaviors

Reckless or risky behaviour can increase following involvement with abortion

Suicidal ideation

Fathers who opposed the abortion may verge on being suicidal themselves. This occurs especially if the father wanted the child and was against the abortion

Alcohol and Drug abuse

This is a common coping mechanism shared by many men. Some will seek assistance through a treatment program, while others continue excessive alcohol and drug use

Emotional abuse and/or spousal battering

This can be man to woman or woman to man. On a subconscious level, this is the scenario of anger and striking out, but it can also be consciously "punishing" the partner for the choice of abortion. Some relationships may deteriorate completely and result in a divorce

Coyle, C. T., PhD. Men and Abortion: A Path to Healing. Lewiston, NY: Life Cycle Books, 1999.

What the experts say

According to psychiatrist Neil Bernstein, men frequently react by "denial and distancing." Those who can get in touch with their feelings, he says, experience abortion with the same range of emotions and ambivalences that women do, including compassion for the partner, guilt about destroying life and disappointment at having made a mistake.

Paterson, Judith. Whose Freedom of Choice? Sometimes it Takes Two to Untangle", The Progressive, 46(1):42-45, April 1982.

Sociologist Arthur Shostak says, "Most of the men I talk to think about the abortion years after it is over. They feel sad, they feel curious, they feel a lot of things; but usually they have talked to no one about it. It's a taboo. It's not accepted for them to talk about it... With the man, if he wants to shed a tear, he had better do it privately. If he feels that the abortion had denied him his child, he had better work it through himself. He does not share his pain with a clergyman, a minister; he does not share it with a close male friend while they're hunting in a duck blind. It just stays with him. And it stays for a long time."

Greene, Bob. "Men Carry Abortion Scars, Too." Human Life Review, Vol. IX No 4, Fall, 1983, pp.103-104, re-printed with permission of Tribune Company Syndicate, Inc., quoting Arthur Shostak

Vincent Rue, Ph.D., pioneer researcher in the field of men and abortion, wrote in an article, The Effects of Abortion on Men, that "men do grieve following abortion, but they are more likely to deny their grief or internalize their feelings of loss rather than openly express them . . . When men do express their grief, they try to do so in culturally prescribed "masculine" ways, i.e. anger, aggressiveness, control. Men typically grieve in a private way following an abortion. Because of this, men's requests for help may often go unrecognized and unheeded by those around them." He continues, "A guilt-ridden, tormented male does not easily love or accept love. His preoccupation with his partner, his denial of himself and his relentless feelings of post-abortion emptiness can nullify even the best of intentions. His guilt may prevent him from seeking compassion, support or affection. In turn, he 'forgets' how to reciprocate these feelings."

Personal stories from post-abortive fathers

Regret of abortion continues to linger

It has been 20 years since my ex-wife and I aborted our first child. I pray every day for forgiveness. I'm fairly certain my former wife is pro-choice in the divisive matter of abortion. I'm certain, as well, that she hasn't realized I've grown to become pro-life. But those labels didn't matter much back in the early 1970s, when we were young newlyweds just starting out. It was like so many things in life. You don't realize the gravity of your actions until later. Often much later. Sadly, it's usually too late to correct the mistakes, if not the sins, of the past.

The news media seldom seem to talk about how men feel when a woman decides to have an abortion. I suspect that's because it's more logical to focus on the woman, since it's her body and her ultimate decision to terminate the pregnancy. Perhaps, too, it's that many fathers - married or otherwise - just don't care enough whether an abortion takes place or not. For me, at least, it isn't like that. All these years later, I still go to bed at night asking God to forgive our decision - a decision, I believe, that was born of the idealism and ambition, but also out of the ignorance and selfishness of youth.

When we were first married, our short-term goals were well defined: We would get good jobs, save our money, buy a house. We always felt that paying a landlord every month wasn't much different from putting a match to that money. So, with our hearts set on buying our first house, nothing was going to stand in our way - including children who came when they weren't planned. In fact, I was not particularly fond of kids at the time at all. Having one of our own was the furthest thing from my mind. But as fate would have it, my wife became pregnant. Long before we knew of her condition, I'd been almost preachy in my repeated desire not to have kids.

My wife made an appointment at Buffalo Children's Hospital and had the fetus aborted. Admittedly, at the time, I had virtually no idea how an abortion was performed. Or rather, I had an idea - but it was not an accurate one. I presumed the procedure was little more than the quick and easy dissolving of some microscopic cells. Clinical and unemotional.

Over the years, of course, I've become far more enlightened on the procedure, realizing there's an all-too-real human dimension to the process. Long after the abortion was carried out, the emotional fallout continues, at least for me. I still occasionally have sleepless nights, thinking about what we did and why.

I've never admitted this to anyone - verbally or in writing - but I've long wondered whether that ill-fated child was a boy or a girl. We were later blessed with two beautiful daughters, now 17 and 13. They are precious beyond words. But who was the child we never knew? Would he have been my son? What would he or she be like today, at 20 years of age? How would I justify either of my teen-age daughters having never been given the chance to be the remarkable young ladies they've become?

Seeing the indescribable joy we share today - how proud their mom and I both are of our children, and the love they give back - it's hard to imagine making the decision we made back then. I tell myself I shouldn't beat myself up over youthful immaturity and bad judgment. I was only in my early 20s, after all, and my wife was barely out of her teens.

Still, the pain of that decision, and the regret, linger. It took being a father of two great kids to make me realize that life truly is a gift. Sometimes I think God got it backwards. He should have given us, as young people, the wisdom we only come to acquire in our later years. Then, perhaps, some of the mistakes of our youth wouldn't hurt so much later on.

PAUL CHIMERA is a Williamsville (USA) independent journalist and teacher. His story appeared in the Buffalo News, New York

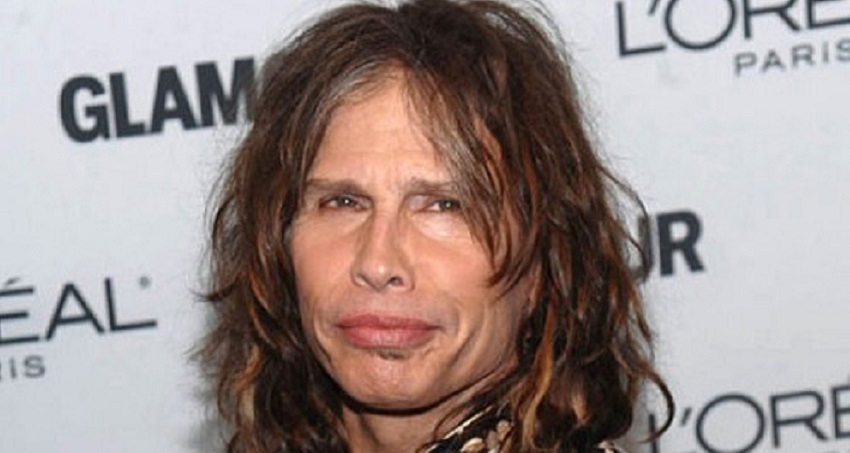

'Jesus, what have I done?': Rock star Steve Tyler's traumatic encounter with abortion

Lead singer of the band Aerosmith, Steven Tyler, confessed to having his child aborted back in the 1970s and shared the details of the trauma that he experienced because of it.

In 1975, Tyler was in his late 20s and persuaded the parents of his 14-year-old girlfriend, Julia Holcomb, to make him her legal guardian so that they could live together in Boston. When Miss Holcomb and Tyler conceived a child, his longtime friend Ray Tabano convinced Tyler that abortion was the only solution.

Tabano said, "They had the abortion and it really messed Steven up because it was a boy. He saw the whole thing and it [messed] him up big time."

Tyler reflected on his abortion experience in his autobiography saying,

It was a big crisis. It's a major thing when you're growing something with a woman, but they convinced us that it would never work out and would ruin our lives...You go to the doctor and they put the needle in her bell and they squeeze the stuff in and you watch. And it comes out dead. I was pretty devastated. In my mind, I'm going: 'Jesus, what have I done?

said Tyler of the abortion.

After the abortion, Tyler had an affair with a Playboy model named Bebe Buell, while remaining in a relationship with Holcomb, the mother of his aborted baby. Buell recounted the effect that abortion had on Holcomb saying, "There were many suicidal calls from poor Diana as they were breaking up. It was actually a pretty sad time"

In the time after the abortion, Steven's life also began to spiral out of control. He went on a European concert tour and was accompanied by Buell, who said, "He was crazy... totally drunk, really out of it... Steven destroyed his dressing room at Hammersmith... when we got back from Europe... One night I found him on the floor of his bathroom having a drug seizure. He was writhing in pain."

There were many days during this time that Tyler was stoned on massive doses of barbiturate. Tyler said, "I would eat four or five [barbiturates] a day... and be good for a couple of months... which is why that period is blackout stuff."

Then, Miss Buell became pregnant with Tyler's child. She realised it would be impossible for her to raise a child with Tyler, given his out-of-control lifestyle and substance abuse. She returned to her former lover, composer/producer/recording artist Todd Rundgren, who agreed to act as father of the child and keep Tyler's fatherhood a secret. Their daughter, who grew up to become actress Liv Tyler, was born on 1 July 1977.

Years later, when Tyler married, and he and his wife were expecting their first child, he said he was still haunted by the abortion. "It affected me later... I was afraid. I thought we'd give birth to a six-headed cow because of what I'd done with other women," Tyler concluded. "The real-life guilt was very traumatic for me. It still hurts."

Read more on the story here...

Remembering Thomas

This year's March for Life in which 45,000 abortion opponents picketed the Supreme Court, didn't have the emotional impact on me that these events often do. I was on my way out of town on business, and scarcely noticed. Looking at reports later it seemed that everyone had been on his or her best behavior. The abortion opponents were making it plain that they oppose the use of violence to close clinics. And counter-demonstrations by abortion rights advocates as we're careful to call them were rare. ...

I like prayer. It's all I have left. And pain.

When the abortion was performed I was out of town on business, too. I made sure of that. Whatever physical, emotional and spiritual agony the woman suffered, I was not by her side to support her. I turned my face away. My behavior was in all respects craven, immoral.

For some instinctual reason, or just imaginatively, I've come to believe that it was a boy, a son whom I wanted killed because, at the time his existence would have inconvenienced me. I'd had my fun. He didn't fit into my plans. His name, which is carved on my heart, was Thomas.

My feelings of responsibility and guilt are undiminished by the fact that the woman had full legal authority to make the decision on her own, either way, without consulting me or even informing me. In fact, she consulted in an open fashion, reflecting our shared responsibility and I could have made a strong case for having the child. Instead, I urged her along the path of death.

And skipped town.

It's not a lot of help, either-emotionally or spiritually-that the high priests of the American judiciary have put their A-OK on this particular form of what I personally have come to regard as the slaughter of innocents. After all, it's the task of government to decide whom we may or must kill, and not necessarily to provide therapeutic services afterward. In the Army I remember being trained at public expense in the "spirit of the bayonet," which is, simply put, "to kill." The spirit of abortion is the same in my view, though the enemy isn't shooting back.

I feel like a murderer, which isn't to say that I blame anyone else, or think anyone else is a murderer.It's just the way I feel and all the rationalizations in the world haven't changed this. I still grieve for little Thomas. It is an ocean of grief.

From somewhere in the distant past I remember the phrase from Shakespeare, the multitudinous seas, "incarnadine." When I go up to the river on vacation this summer, he won't be going boating with me on the lovely old wooden runabout that I can't really afford to put in the water but can't bring myself to discard, either.

He won't be lying on the grass by the tent at night looking at the starry sky and saying, "What's that one called, Dad?" Because there was no room on the Earth for Thomas. He's dead.

The latest numbers show abortions in America have been running at about 1.5 million annually. That's a lot of pain.

Secular men's groups have tended to be focused on the "no say, no pay" issue. "These men feel raped," says Mel Feit of the National Center for Men. "They lose everything they worked for all their lives. In many cases they had an agreement with the woman not to have a baby and when she changes her mind they call me up and say, "How can she do this to me? How can she get away with it?" Feit plans to bring suit in federal court.

I'm more interested in the traumatic pain that many men, as well as women often feel after an abortion. A healing process of recognition, grieving and ultimately forgiveness is needed. "There's a lot of ambivalence for men when they get in touch with their pain," says Eileen C. Marx, formerly communications director for Cardinal James A. Hickey of Washington and now a columnist for Catholic publications. "They didn't have the physical pregnancy, so often they feel they're not entitled to the feelings of sadness and anger and guilt and loss that women often feel."

She tells of one man, a friend, whose wife had an abortion. "He pleaded with her not to have it. He said his parents would raise the child, or they could put it up for adoption. The marriage broke up as a result of the abortion and other issues. He was really devastated by the experience."

Marx has recently written about a post-abortion healing ministry called Project Rachel in which more men are becoming involved-husbands, boyfriends and even grandfathers. There are 100 Project Rachel branches, including one in Washington.

I found it helpful just talking with Marx, a caring person, on the phone: though it was a little tough when she mentioned being pregnant and hearing the heartbeat and feeling "this wonderful celebration of the life inside you." She said not to be too hard on myself, that healing is about forgiveness and God forgives me. I said sure, that's right but some things are still hard. Like looking in the mirror.

PHIL MCCOMBS story appeared in the Washington Post, 3 February 1995

The Secret I Buried for 20 Years

In front of 2,200 Baylor University students, I confessed a sin: "Twenty years ago I came to this school to get a Christian education, but what I got was a girl pregnant my first year here."

Being invited to speak at my alma mater was a great honor. As I thought about how I could challenge these students, it would have been more fun to play up my accomplishments. But I had to admit who I really was and what I had done.

Twenty years ago, I helped pay for my girlfriend's abortion. My immediate reaction to her news was it was an inconvenience that must be eliminated. I never stopped to think about what I was doing. I never considered that a real life was inside her that I had helped create. I simply thought the doctor was removing some unwanted tissue.

My wife and I struggled with infertility. Once I could create life, but ended it. Now I could do neither. Years later I faced the truth. I had selfishly destroyed a human life because I didn't want to be inconvenienced. My rude awakening was "male post-abortion syndrome," a flood of guilt, confusion, and denial that often follows an abortion.

Post-abortion syndrome is typically associated with mothers of aborted children, but I'm one of the thousands of abortion fathers who have also gone through this ordeal. In my case, it resulted in 80 ulcers eating at my stomach, intestines, and colon. The pain was excruciating and made worse by the knowledge that it was a result of my secret sin. Accepting God's forgiveness through Jesus Christ was the miracle I needed. Over time the internal physical scars disappeared; subsequent tests revealed no trace of the trauma. The guilt of my secret sin had destroyed my health. However, God restored it.

Shortly after speaking at Baylor, the woman I had gotten pregnant more than two decades earlier called me. She had heard about my talk. It was wonderful to hear that she, too, had experienced God's healing from that horrible act.

She had only one suggestion: "The next time you tell the story be more honest about what really happened. You didn't just help pay for the abortion; you pressured me to get it."It was true. She never wanted to do it. She wanted to keep the baby. It was my forcefulness that finally led her to do what she didn't want to do.

I came face-to-face with who I really was – a coward who preyed upon someone else to make my own life easier.

Studies show the most significant factor in a woman's decision to get an abortion is lack of support from the man to keep the child. As painful as it was hearing it, I was glad this friend from years ago had the courage to confront me.

Steve Arterburn, Author, Radio Show Host and Counsellor

'Nowhere to go': Former 'Cats' Broadway actor describes heartbreak after abortion

A former rising star on Broadway has shared how the abortion of his child sent him on a downward spiral that engulfed him in despair. Canadian performer David MacDonald, 50, gave his testimony at a gathering of Silent No More Awareness following Canada's March for Life in 2011, where several other men and women also described their abortion trauma.

Once a powerful singer, MacDonald's voice at the podium sometimes barely rose above a squeak - his vocal cords destroyed, he says, because of the stress he suffered following the abortion of his girlfriend's baby when MacDonald was 21.

When MacDonald first learned his girlfriend was pregnant, he thought abortion was the obvious answer.

I didn't want to hear that [she was pregnant], you see ... I didn't want the responsibility, I wanted the sex, and so the easy way out was abortion. That's what I thought. Just pay $300 and the problem goes away.

"Life is priceless. You can't put a price on it. I tried to put a price of $300 on my child's life. It didn't work."

MacDonald said his girlfriend was "completely devastated" by the abortion, which also drove MacDonald deeper into a life of drugs and promiscuity. "There's nowhere to go when you've made a mistake like that and you don't know Jesus, so I just kept running to all these different places," he said.

MacDonald said that he met success co-starring in movies for Paramount and Columbia Pictures, and landed a "dream job" as the Rock & Roll Cat in the US National Tour of "Cats." But his career came to an abrupt halt one day when he pushed his voice far too hard despite being sick.

"That was the end of my voice, and that was the end of my career," he said.

The journey to healing from the abortion, he said, was a long, long, long hard road, but it began with getting on my knees. My life was without God, and without god you have nothing.

I wanted to die

"Within 60 days I was in what I now call the 3 D's - Drugs, Daring, and Death and that is where I remained for three years. I was doing drugs constantly - 24 hours a day. I never was straight. I went to church stoned. I went to my job stoned. I also ruined my career. I was living on the edge of a daring life. I was the guy you saw on the ski slopes coming down missing the trees, doing flips and hitting those moguls at 90 miles per hour. I was driving fast and drinking and driving because I had lost my self-worth. I had everything bottled up within me. I was waiting for life to be snatched from me because it had lost its meaning, and I wanted to die to atone for the one I had allowed to be taken."

Paterson, Judith. Whose Freedom of Choice? Sometimes it Takes Two to Untangle", The Progressive, 46(1):42-45, April 1982.

That could have been my little David Beckham.

TOWIE'S Mark Wright says he sobbed when ex Lauren Goodger aborted their unborn child, adding: "That could have been my little David Beckham." Mark said he and his ex-fiancée made the decision "100 per cent together" as teenagers.

But he blasted Lauren for revealing their "sad and personal" decision — and vowed never to get back together with her.

Op-Ed: Where are all the men?

Several weeks ago, one of my friends from Vancouver contacted me to ask for advice. A girl she knew was planning to have an abortion, and my friend needed advice on what to say. Over the next two weeks, I and another one of my pro-life friends from Vancouver, attempted to help her in convincing this young woman not to abort her child. The girl, initially open to discussion, had her phone taken away by her boyfriend, and was eventually coerced into having an abortion by a man who saw his own future as more important than the offspring he had fathered.

This is when a question struck me: what has manhood in today's culture become when two girls in Vancouver are fighting harder for the life of a child than his or her own father?

Links

- I wish I could have prevented my girlfriend's abortion

- 10 years ago I lost an unborn child to abortion

- How I became prolife