NEW study on maternal mortality estimates shows education level a key consideration

A new study published in the Journal of Public Health has shown that estimates of maternal deaths should be more focused on one particular variable - women's education level.

The study, from researchers at the MELISA Institute, examined how accurate or reliable estimates of maternal mortality were, and found that there were major discrepancies in estimates made in global reports. These estimates were shown not to be always accurate in the study.

Having an accurate record of the number of women dying in pregnancy or after childbirth is a key factor in improving maternal healthcare services worldwide, and gathering accurate information in relation to the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is key.

Some countries have incomplete vital statistics leading to a situation where maternal deaths are estimated, usually using mathematical models which consider variables such as delivery by skilled attendants, per capita income etc.

This has led to a situation where the accuracy of estimations have been called into question, in particular where the estimates are being used to draw conclusions in relation to changes required in providing maternal healthcare.

Abortion advocates, for example, sometimes claim that maternal mortality will rise where abortion is banned, despite the evidence to the contrary from the Chilean Experience and from Ireland, where the Dublin Declaration stating that abortion is not medically necessary was issued, has now been signed by more than 900 medical professionals.

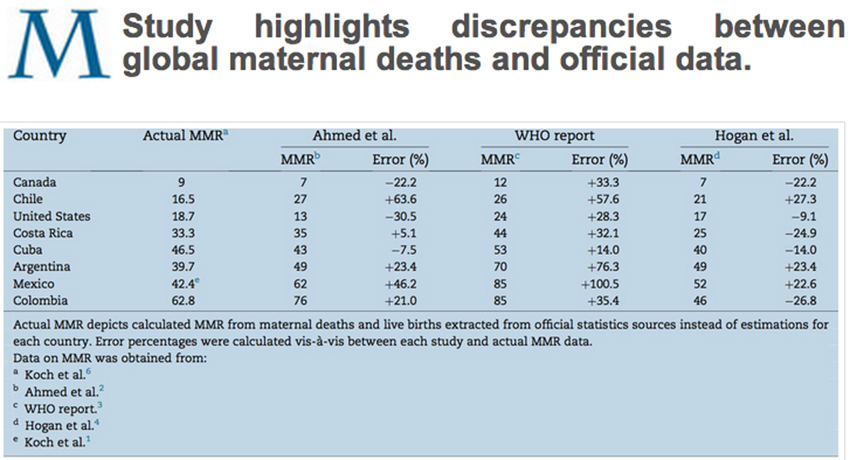

The MELISA institute looked at two recent global reports which showed discrepancies between 14% and 100% when compared with official maternal mortality figures from the countries evaluated. They pointed out that, in contrast, a third independent report, by Hogan et al., conducted by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington, published in The Lancet was considerably more accurate. The researchers analysed the estimates from all three reports and compared them with official figures calculated on the babies of reliable vital statistics from eight American countries.

In Mexico, for example, a country who the World Health Organisation says has reliable civil registrations, the official figures show a MMR of 42 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2010 but the WHO's own estimate for that year was 85 maternal deaths per 100,000 - a discrepancy of 100%. A global report from Ahmed et al. also shows a discrepancy of 46%. The authors of the study also found a similar pattern of discrepancies in seven other countries, all recognised as having reliable vita statistics including Chile, Argentina, the US and Canada. They also found the third study - by Hogan et al - to be the most accurate and to have the least discrepancies.

According to the researchers, the reason for this seemed to be that Hogan et al. included an important variable - women's educational level - and this apparently increased the accuracy of maternal death estimates. Another recent study conducted in Chile identified the level of female education as a main determinant of the progress in maternal health for the past 50 years, with synergistic effects on other variables such as access to prenatal care, fertility rate, and childbirth delivery by skilled personnel. The MELISA Institute suggests the use of official data from countries with reliable records, reaching 67 according to the latest maternal mortality report drafted by the UN in 2013. If reliable records are unavailable, estimation models considering women’s education level should be preferred.

AN EXAMPLE SHOWN BELOW

WATCH THIS EXPLANATORY VIDEO

LINKS

See the Melisa Institute Press Release

See the Study on Maternal Mortality discrepancies

Featured

- Canada to reach 100,000 deaths by Assisted Suicide

- Pro-Life Street Event is a Powerful Witness

- Calls for inquiry: 108 babies born alive then die after abortion

- Britain: Assisted Suicide Bill ‘will almost certainly fail’

- Every Life Counts: sending love and care for sick babies

- "A step backwards": Jersey has legalised Assisted Suicide

- 8,000 babies saved by Abortion Pill Reversal

- Spain Moves To Restrict Pro-Life Protests Near Abortion Clinics

- Mediums and abortion: a dangerous narrative

- Man jailed for 9 years for forced abortion

- Abortion coercion has arrived in Ireland – the NWC are silent

- Review of at-home abortions 'needed after coercion case'

- French Govt to remind 29-year-olds of biological clock

- Rally for Life 2025

You can make a difference.

DONATE TODAY