History's greatest social reformers weren't 'nice.' Pro-lifers shouldn't either

If there’s any word I’ve grown to hate during my years of pro-life work, it’s the word “nice.” We must be “nice,” people urge us. If we are not “nice,” our activism and our outreach will fail. If we are not “nice,” then no one will change their minds on abortion or listen to us. If we are not “nice,” we will never achieve a pro-life consensus.

This is, quite bluntly, not true. We must be compassionate, absolutely. We must be charitable, without doubt. We must be truthful—this is essential. If that is what we mean when we use the word “nice,” then I agree completely. But that is not what the critics of pro-life activism actually mean.

They mean we are being controversial. And indeed, how can we not be? The majority of Canadians, for example, are pro-choice. And further, a majority of Canadians do not want to discuss the abortion issue at all, for obvious reasons. Abortion is a very uncomfortable topic. The gruesome reality of abortion—that it results in the physical destruction of a developing human being—is shocking and disturbing. People do not like being shocked and disturbed, and thus they prefer the discussion that conjures up such feelings to go away. The debate be “closed,” abortion advocates like to prematurely announce.

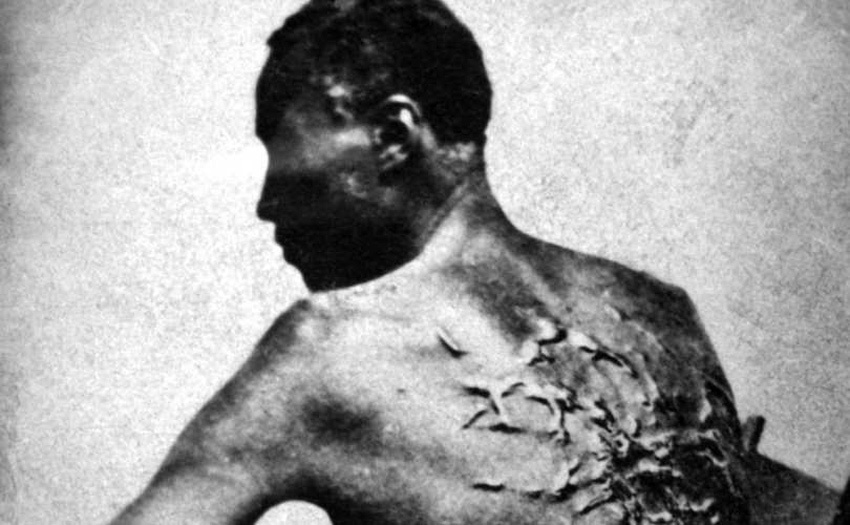

This photo isn’t “nice.” It makes me intensely uncomfortable. As it should. And that’s why it helped contribute to the end of slavery.

And they also mean we are being confrontational. But again, how can we not be? We live in a nation that has been more or less at peace, with the exception of a dedicated minority, with the fact that we have ended the lives of more than three million tiny humans, shredded in the womb and discarded like so much garbage. Indeed, for the most part, we are even at peace with the fact that the Canadian government garnishes our wages to fund this barbarism. Even the words seem shocking—these are not very “nice” things to say. And yet, they are true and must be spoken. Lives literally depend on it.

But Canadians don’t respond well to such controversial tactics as exposing the reality of abortion through powerful imagery, we are told. This, of course, simply isn’t true—thousands of face-to-face conversations with Canadians about abortion have shown us that while they may not want to have the discussion, many of them change their minds on this issue when that discussion takes place. I have photos of babies that were, once upon a time, scheduled to be aborted by “nice” Canadian doctors as proof of that.

In the context of abortion, the much-vaunted Canadian politeness is invoked as a reason to avoid confrontation. I’d like to think that Canadians are not so polite that they would avoid waking up their neighbor to inform him that his house is burning down.

Shouts of warning may disturb his slumber, yes, but sometimes our comfort can prove lethal.

It is important to remember that when we bring up a disturbing topic like abortion, violent reaction is often inevitable. That is not a by-product of using abortion imagery, it is a by-product of the violence abortion culture brings with it. One of my friends was punched in the face for sidewalk-chalking friendly pro-life messages. A woman at Life Chain in Toronto was assaulted by a man furious that someone was exposing the truth about abortion. And as any pro-life activist engaging the public in any way can attest, the subject alone is the source of tension that we know must exist. It is, after all, why we’re doing outreach in the first place.

As the philosopher Arthur Schopenauer once said, “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as self-evident.” Unfortunately, many people want to skip from being ridiculed to being vindicated, without accepting the inevitable persecution that will occur first.

We seem to have forgotten the history of social reform movements, and the hardships and backlash that activists had to endure in the past.

Because Martin Luther King Jr., and William Wilberforce, and Lewis Hine, are all considered heroes now, we forget that in their day, they were often widely despised and hated. King and the Civil Rights activists endured a level of physical violence that pro-lifers can scarcely imagine. Wilberforce’s abolitionists were regularly threatened, and his right-hand man Thomas Clarkson was once nearly thrown off the docks in Liverpool by angry slave traders. Lewis Hine, the photographer who displayed pictures of child laborers, was opposed by the forces of American industry who despised him for his exposure of their brutal practices. And I could list so many more.None of these men, none of these activists, none of these movements were considered “nice.” Using shocking imagery and disturbing evidence, they forced a cultural discussion that nobody wanted to have. They confronted their societies with truths no one wanted to hear. They suffered much ridicule, hatred, and even violence as the result of that. All of them were warned that their tactics would not succeed because they were controversial, or divisive, or “not nice.” But they recognized that without confronting the culture, they would never change the culture.

When pro-life activists engage in campaigns like our #No2Trudeau Campaign, where we plan to distribute a million pieces of literature highlighting the legal destruction of human life in Canada, make thousands of phone calls to Canadians on this issue, and work to rebuild a pro-life consensus in this country, we realize that the politicians will be uncomfortable. We realize that many people will not want to discuss this most important of issues. And we realize that abortion activists and the media will do everything in their power to discredit what we are doing and to downplay any results.

But pro-lifers have to realize that controversy is inevitable, that confrontation is necessary, and that backlash is inevitable. Millions of Canadians have no idea what abortion is. Abortion culture has flourished in darkness. And when you turn the light on in a room that has been dark for a very long time, often it hurts the eyes.

That may not be nice. But it is the truth.

Jonathon Van Maren writes on the Bridgehead blog and is this article is printed here with his permission

Featured

- Calls for inquiry: 108 babies born alive then die after abortion

- Britain: Assisted Suicide Bill ‘will almost certainly fail’

- Every Life Counts: sending love and care for sick babies

- "A step backwards": Jersey has legalised Assisted Suicide

- 8,000 babies saved by Abortion Pill Reversal

- Spain Moves To Restrict Pro-Life Protests Near Abortion Clinics

- Mediums and abortion: a dangerous narrative

- Man jailed for 9 years for forced abortion

- Abortion coercion has arrived in Ireland – the NWC are silent

- Review of at-home abortions 'needed after coercion case'

- French Govt to remind 29-year-olds of biological clock

- Rally for Life 2025