The Abortion Referendum One Year On: Reflections on a Eucharistic Imperative

Commemorations are rarely straightforward events.

More often than not they are imbued with contested narratives or ongoing conflicts related to their meaning or importance.

This remains true whether we are speaking of national events like those surrounding the 100th Anniversary of the First Dáil in 1919 or the local celebration of a memorial service for a fractured family or community.

Such contestation and conflict is also highly likely to emerge with respect to the ways in which different groups choose to mark or assign value to the passage of controversial legislation or the outcomes of divisive referendum campaigns.

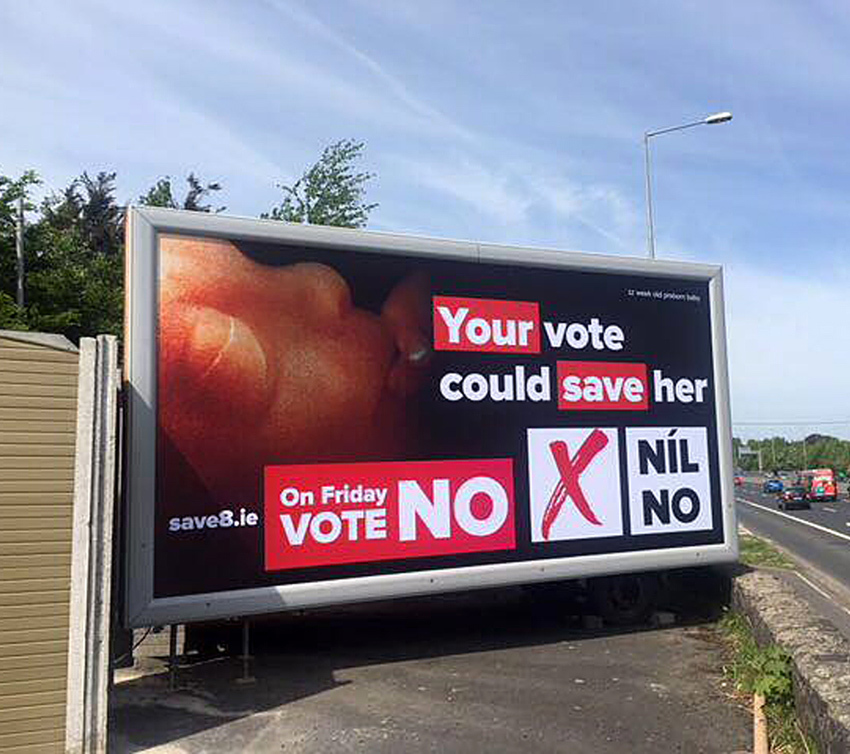

Nowhere will this be more apparent in the coming weeks than on 25th May, the first anniversary of the referendum that successfully removed the pro-life Eighth Amendment from the Constitution.

For very many people this anniversary will be filled with pathos as they reflect on the categorical, dehumanising and tragic error of judgement that it recalls.

This will be especially true if it is greeted with macabre celebratory scenes similar to those that took place in Dublin Castle after the outcome of the referendum was originally confirmed.

For others, and despite all its inconsistency, the vote will continue to be interpreted as a necessary ethical leap towards the creation of a society that is more ‘compassionate’ and sensitive to the nuance that fills people’s lives.

For the majority of those at the political level however, the decision taken last May appears to have acted as a kind of licence for the promotion of a constricting and narrowly circumscribed view about what does, and what does not constitute legitimate democratic engagement.

This view has already proven itself to be profoundly consequential in terms of our capacity to keep the right to life of the unborn in the public awareness and in political conversation.

If left unchallenged it will serve to empty the public square of critical or contrary voices.

To be specific; two things are being referred to here.

The first is the approach to the pro-life issue that crystallised with disturbing clarity during the course of the Oireachtas debates on the 2018 abortion legislation and which has subsequently gained significant political momentum.

The second is the parallel drive to herd expressions of the Christian ethos into the increasingly crowded pen of the private sphere.

With respect to the first challenge; what we have seen emerge is a distinct emphasis on the proposition that further debate on the pro-life question is now effectively over.

This has gone way beyond the usual and platitudinous references to respect the fact that ‘the people have spoken.’

In fact it is rapidly approaching that attitude originally described by the political philosopher Eric Voegelin, as “the prohibition of questions.”

To rescue this claim from hyperbole one need only review how often the tiny political minority who sought to amend the extreme nature of the abortion legislation were shouted down, while being arraigned before the court of public and parliamentary opinion as enemies of the people.

That one pro-choice TD described this minority’s efforts to gather typical and confidential data on the incidence of abortion rates and the abortion methods employed as tools of an Apartheid regime, only serves to hint at the difficulties that will be faced in the years ahead.

In light of this, one of the greatest challenges for the pro-life cause will be that of persuading public representatives of the importance of retrieving the issue from the self-imposed and suffocating political finality that it has been subjected too in the last year.

In the absence of this it will surely become almost impossible to raise deeper questions such as; is it ever legitimate to place the obliteration or retention of fundamental or antecedent human rights into the hands of the majority?

In terms of the second challenge mentioned above, that of relegating public expressions of the Christian ethos to the private sphere, we need only observe two development that have also taken place over the course of the last year.

The first is the strength of the cross party political support for recommendations related to the revision of relationships and sexuality education in all schools and centres of education from primary to tertiary level.

These recommendations, contained in the Oireachtas Education Committee Report on the issue, are unequivocal in their assessment of the Christian ethos; characterising it as a barrier and an inherently deficient vehicle for publicly communicating the ‘right’ perspective on matters like gender theory or the positive promotion of abortion as ‘reproductive healthcare.’

That this amounts to a form of pedagogical myopia is clearly established through the Committee’s reaffirmation of the view originally put forward by the Joint Oireachtas Committee on the Eighth Amendment, i.e. that such education should be mandatorily provided “independent of ethos.”

This approach, which seems determined to set schools and Christian parents on a direct collision course with the state, will have clear consequences in terms of our capacity to politically advance and nurture the right to life of the unborn child.

Is it too much to suggest that such action amounts to a de facto first step on the road to prohibiting any institution, with even the most tangentially public role, from seeking to shape its internal life or mode of operation according to principles based on the Christian ethos?

The second development that demonstrates the government’s willingness to aggressively pursue and even criminalise peaceful and prayerful pro-life ‘protest’ can be seen in the decision to introduce ‘Exclusion Zones’ around facilities that provide abortion services.

That such proposed legislation is in direct conflict with lawful freedom of expression and peaceful assembly speaks yet again to the attitude identified by Voegelin as the prohibition of questions.

There can be little doubt then that efforts are under way to insulate the states ideological position on the abortion issue from any challenge; no matter how benign that challenge is.

Clearly all of this presents significant and concrete challenges in terms of keeping the right to life a feature of civil and political discourse.

This does not mean of course that we should simply resign the task and acquiesce in the political call to inflict upon ourselves a self-imposed silence.

Indeed there is simply too much at stake to allow ourselves, at an individual level, to cowed by that kind of specious reasoning which seeks to equate speaking up for a culture of life with the promotion of an anti-democratic impulse.

This is also true when it comes to protecting the capacity of the Church in the public sphere to maintain and promote its own evaluative stance on measures that touch upon the fundamentals of human dignity.

To conclude; as members of the Body of Christ we are in the privileged position of recognising that memorialisation-the union of memory and action-is at the heart of Christian witness and never more so than when it is linked to the death or suffering of the innocent.

In light of that, it might be argued there is something of a Eucharistic imperative to engage with this upcoming anniversary and the challenges that it presents to us.

We should not allow it to be passed over in silence while at the same time yielding the public space to those who seek only to frame the practice of abortion as synonymous with a certain kind of liberation.

Instead we can try and develop a response in line with the powerful reminder offered to us by St John Paul the Great: “Do not give into despair. We are an Easter people and Alleluia is our Song.”

This piece first appeared in the May 2019 edition of Intercom https://www.intercommagazine.i...

Featured

- Every Life Counts: sending love and care for sick babies

- "A step backwards": Jersey has legalised Assisted Suicide

- 8,000 babies saved by Abortion Pill Reversal

- Spain Moves To Restrict Pro-Life Protests Near Abortion Clinics

- Mediums and abortion: a dangerous narrative

- Man jailed for 9 years for forced abortion

- Abortion coercion has arrived in Ireland – the NWC are silent

- Review of at-home abortions 'needed after coercion case'

- French Govt to remind 29-year-olds of biological clock

- Huge factor in decline in primary school numbers ignored

- Germany Denies Promoting Abortion Abroad—While Funding Pro-Abortion NGOs

- Govt don’t oppose Coppinger abortion bill at 1st stage

- March for Life: Vance, the White House, and a Divided Pro-Life Movement

- Paris’ Annual March for Life Puts Euthanasia in the Spotlight

- Britain’s seemingly limitless abortion rate

- The importance of the work carried out by Every Life Counts

- Puerto Rico officially recognizes unborn children as ‘natural persons’

- Rally for Life 2025