Didion On The Death Of Children

Joan Didion died at the age of 87 in her Manhattan home on December 23, 2021. She was one of the great American pioneers of creative non-fiction, along with Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, and Truman Capote. Like all of them, she became as famous for her distinctive persona as for her prose. She arguably did for the ’60s in California what Wolfe did for the ’80s in New York in The Bonfire of the Vanities. She was one of the few writers who gazed into the abyss and took notes instead of blinking, and she produced some of the era’s best writing as a result.

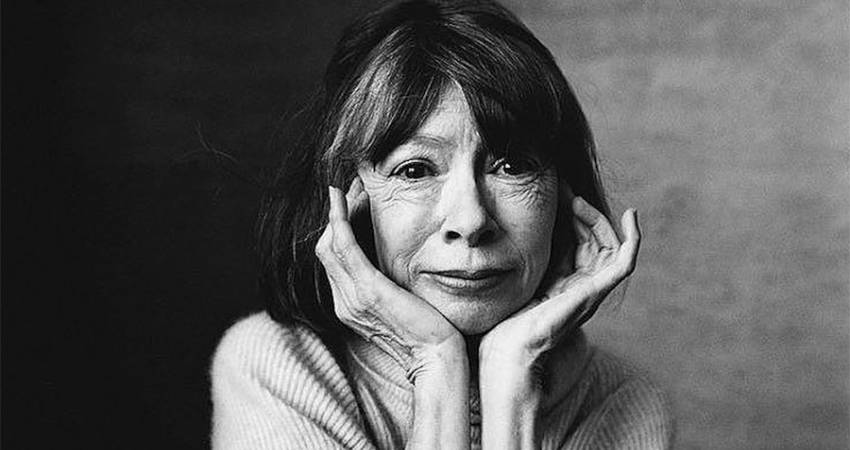

Didion’s last major public foray came not in the form of prose, but in the 2017 documentary Joan Didion: The Center Cannot Hold. An elderly, vibrant Didion tells her story—but it somehow doesn’t seem quite like her. Didion’s decades-long career is frozen in the collective imagination at the moment she broke into public consciousness: Her wide-eyed, elfin looks—the sort that make men feel instinctively protective—had an almost defiant vulnerability, wreathed in a halo of cigarette smoke. She had an aura of tragedy that reflected a culture wrecking itself around her.

“The center cannot hold” is from William Butler Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming,” and Didion used an amended version of the closing line—Slouching Towards Bethlehem—as the title of her 1968 book of essays. It is a chilling collection chronicling the disorder of those heady, drug-fueled days when, as she would put it later, it seemed as if America’s social contract was falling apart before her eyes as she took careful notes, composed searing prose, and coolly smoked cigarettes. California was the epicenter of a cultural revolution, and Didion’s groundbreaking reportage detailed the dark side.

But it is her writing about abortion that is perhaps the most haunting. One critic accused her of being “morally obsessed” with it, and perhaps that is because nothing so succinctly symbolizes the rupturing of the social contract brought about by the sexual revolution as the rejection of an innocent unborn child by her mother, the trauma of forced feticide, of passion ending in carnage. She was once asked by an interviewer from the Paris Review why abortion was a recurring theme in her writing. “The death of children worries me all the time,” she replied. “It’s on my mind. Even I know that, and I usually don’t know what’s on my mind.”

Didion never politicized the issue (in “On Morality” she condemned the habit social movements had of trying to “assuage our private guilts into public causes”), but her handling of the subject in her 1970 novel Play It as It Lays is a glimpse into her views. Maria Wyeth, a 31-year-old former actress, narrates from a sanatorium after her life has spiraled out of control with sex, drugs, and a botched abortion (from which she suffers intermittent bleeding). She is separated from her film director husband and her child, who has been institutionalized. The trauma of the abortion gives her nightmares about dying children, perhaps triggered by the doctor’s chilling words during the operation: “Hear that scraping, Maria?”

The abortion is forced on Maria, and thoughts of her lover remind her of the child even when she “tried to stop thinking about what he had done with the baby. The tissue. The living dead thing, whatever you called it.” The italics are Didion’s. She ends the relationship with him, because after the death of the child they conceived together, she feels that “there’s no point” because “she had left the point in a bedroom in Encino.” The point Maria refers to is the child who died in the illegal abortion that wounded her physically, spiritually, and psychologically. Didion drives home this point hard—one of Maria’s nightmares analogizes abortion to the Holocaust.

Above all, Maria is tortured by the yawning absence of the baby who was scraped out of her:

She could not read newspapers because certain stories leapt at her from the page: the four-year-olds in the abandoned refrigerator, the tea party with Purex, the infant in the driveway, rattlesnake in the playpen, the peril, the unspeakable peril, in the everyday.

This is not the only abortion Didion described in her books—the 1963 novel Run River (her first) also features one of the main characters having an abortion. But the raw brutality and keen trauma of the feticide in Play As it Lays surpasses her other work on the issue. Play As it Lays was also more autobiographical—in The Center Cannot Hold, Didion notes that “Maria was quite a bit of myself.”

How autobiographical was it? We can’t know for sure, of course. But in The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion by Tracy Daugherty, her biographer suggests that Didion had an abortion while dating Noel Parmentel, a New York literary figure, in her 20s—and that this both shaped her personal views of abortion and caused her later infertility. When asked about this in interviews, her friends tactfully declined to answer the question. Unable to have children of their own, Didion and her husband John Gregory Dunne adopted a daughter, Quintana Roo.

Joan Didion never openly picked a side in the abortion wars, but she was seen by many (although most of her obituaries have managed to completely avoid mentioning this) as a fundamentally conservative writer. She wrote for William F. Buckley’s National Review, ruthlessly exposed the fantasies of the leftist movements springing up like mushrooms after rain, and noted of the pro-abortion feminist movement in 1972: “To those of us who remained committed mainly to the exploration of moral distinctions and ambiguities, the feminist analysis may have seemed a particularly narrow and cracked determinism.”

When asked by one interviewer why she called writing “a hostile act,” Didion explained:

It’s hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture. It’s hostile to try to wrench around somebody else’s mind that way. Quite often you want to tell somebody your dream, your nightmare. Well, nobody wants to hear about some else’s dream, good or bad; nobody wants to walk around with it. The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to the dream.

One of Joan Didion’s nightmares was about the death of children, and it is a nightmare that should haunt us all.

This article was printed with the author's permission and was first published here

Photo Credit: Tradlands on Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/...

Featured

- Calls for inquiry: 108 babies born alive then die after abortion

- Britain: Assisted Suicide Bill ‘will almost certainly fail’

- Every Life Counts: sending love and care for sick babies

- "A step backwards": Jersey has legalised Assisted Suicide

- 8,000 babies saved by Abortion Pill Reversal

- Spain Moves To Restrict Pro-Life Protests Near Abortion Clinics

- Mediums and abortion: a dangerous narrative

- Man jailed for 9 years for forced abortion

- Abortion coercion has arrived in Ireland – the NWC are silent

- Review of at-home abortions 'needed after coercion case'

- French Govt to remind 29-year-olds of biological clock

- Rally for Life 2025