Assisted suicide in Canada's accounted for 7% of Quebec deaths in 2022

In Dickens’ enduring classic, ‘A Christmas Carol’, the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge, asked to assist those who were in desperate need but who would rather die than face the cruelties of the workhouse, delivers a tremendously pitiless response.

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

That sheer callousness of the miser’s remarks came to mind earlier this year when a poll found that more than a quarter of Canadians would permit assisted suicide in cases where a person was either homeless or living in poverty.

In addition, half of Canadians would agree to allow requests for assisted suicide “due to an inability to receive medical treatment (51%) or a disability (50%)”, the poll found.

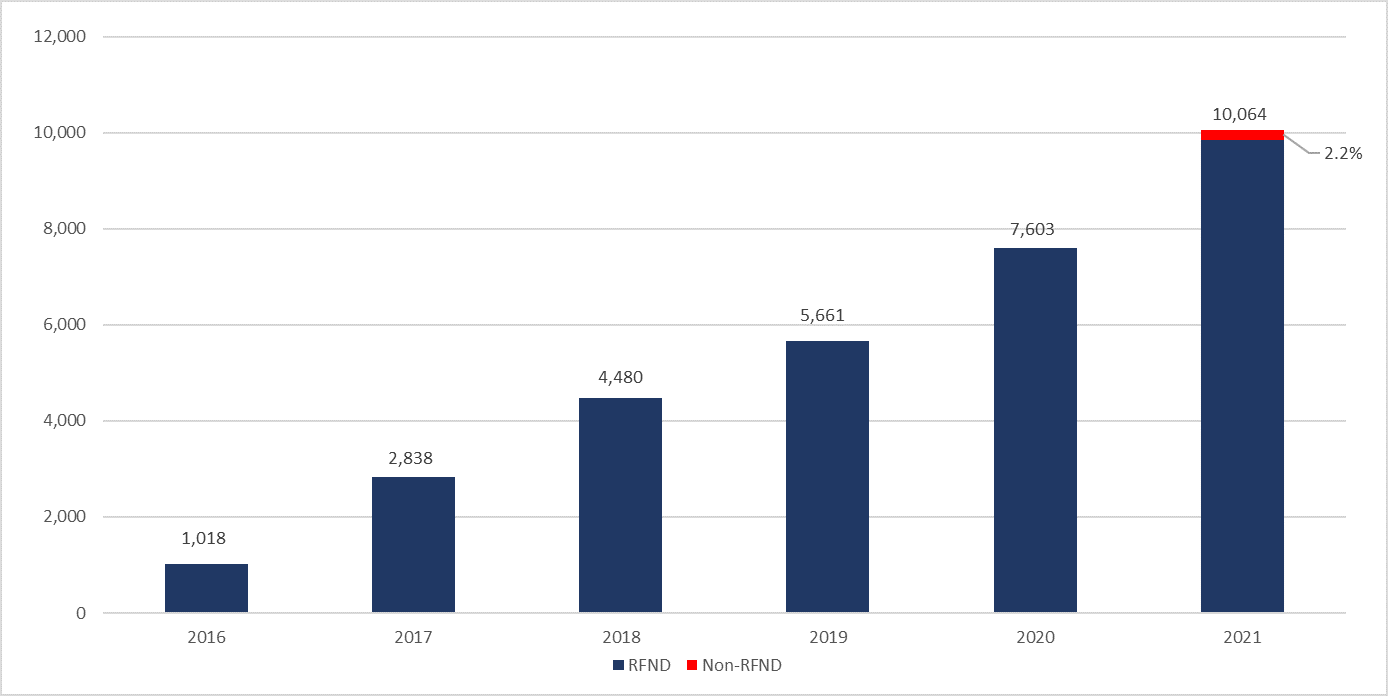

The poll was taken against a background of Canada’s race to embrace assisted suicide, with rates rocketing since it was first introduced in 2016, supposedly as a measure to help those in very difficult circumstances, though – as was predicted – the slippery slope, at lightning speed, became more like a polished luge run.

An amendment to the 2016 law has since ensured that those who were not terminally ill could request assisted suicide, and now state-sanctioned suicide for those who have a mental illness is on the way.

Canada prefers to coyly describe what’s happening as ‘medical assistance in dying’ but the cruel reality of what is happening cannot be denied. Those who are most vulnerable are being helped – sometimes perhaps persuaded – to take their own lives.

In the second year of provision, rates of assisted suicide doubled, and then almost doubled again in 2018. But the numbers have kept accelerating, year on year.

“If they would rather die,” as Scrooge said, “they had better do it” – though what is becoming more and more evident is that assisted suicide is being seen as a means for the authorities to avoid their responsibilities to the poor, the elderly and the most vulnerable.

By 2021, the numbers had increased ten-fold – a startling jump, no doubt pushed higher by the changes in the law – and in attitudes towards those most in need.

In that year, according to the Canadian government, assisted suicide deaths accounted for 3.3% of all deaths in Canada in 2021, an increase from 2.5% in 2020 and 2.0% in 2019.

However, the state’s helping hand in ending one’s life accounted for 4.8% of deaths in British Columbia – and preliminary figures calculated this year suggest that the numbers have worsened again.

Calculations based on state figures from the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition showed another big jump in deaths, with an expected 13,500 deaths from assisted suicide in 2022.

The Coalition says that in Quebec, 7% of all deaths came about by assisted suicide.

Even for the most diehard ideologue, is there not a point where this becomes alarming? What is there to celebrate about a cumulative total of tens of thousands of people killing themselves, mostly because they don’t want to be a burden or they can’t get comfort or support?

Palliative care experts – those who work to care for people who have terminal illnesses and are at the end of their lives – have repeatedly disputed the claim that assisted suicide is necessary for “dying with dignity”.

They say that modern medicine means “ensuring that good care lead to minimal pain or discomfort, rather than ending the patient’s life.

The Canadian state’s figures show that, in 2021, 86% of those seeking assisted suicide cited the loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities – followed closely by the loss of ability to perform activities of daily living at 83.4%.

As has been seen elsewhere, significant numbers also wish to avoid being a burden – truly a sad state of affairs and indicative, perhaps, of an increasingly atomised society.

Canada’s Minister for Health said he was “proud” to present the 2021 Annual Report on assisted suicide. He should be ashamed.

What Canada is ‘proud’ of is actually state-sponsored suicide – the authorities will literally assist you to kill yourself – but it has been successfully wrapped up in that strange inversion of compassion that directs so much of public policy nowadays.

Canada is famed as being a bastion of liberalism. The country’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, is woke to the point of parody, though his progressive star power has been tarnished by numerous controversies including a cash-for-access scandal, accusations of groping, and charges of elitism.

In 2019, when pushing to expand the assisted suicide provision, Trudeau assured voters that that those seeking to have their lives ended would not be motivated by a lack of “the supports and cares that you actually need”.

But the evidence contradicting that claim is mounting, and much of it is horrifying.

An excoriating review of the Canadian experience found multiple stories describing “a system that does encourage the vulnerable to seek medical death”.

A number of recent news articles have reported on Canadians who, driven by poverty and a lack of access to adequate health care, housing, and social services, have turned to the country’s euthanasia system.

In multiple cases, veterans requesting help from Veterans Affairs Canada — at least one asked for PTSD treatment, another for a ramp for her wheelchair — were asked by case workers if they would like to apply for euthanasia.

What does it say about a rich and prosperous country like Canada that the sick and the elderly can’t get the support or engagement they need to continue with their lives?

And does the move towards normalising euthanasia have an underlying, unspoken understanding that assisting people to die can be cheaper than providing healthcare?

Consider the case of Roger Foley from Ontario, who suffered from an incurable neurological disease. In 2018, he made audio recordings of hospital staff offering him medically assisted death, although he had actually repeatedly asked for assistance to live at home.

He was told he would be charged 1500 dollars a day if he continued to take up a bed in the hospital. It was horrifying.

The Life Institute has pointed to a paper published in a leading Canadian medical journal which claimed that millions could be saved in reduced health care spending by ‘medical assistance in dying’.

It “could result in substantial savings”, the authors noted approvingly. The paper was entitled “Cost analysis of medical assistance in dying in Canada” and was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

“If Canadians adopt medical assistance in dying in a manner and extent similar to those of the Netherlands and Belgium, we can expect a reduction in health care spending in the range of tens of millions of dollars per year,” it claimed.

The emergence of such attitudes should be ringing alarm bells in Health Canada and in the legislature, but they may be considering instead the report from the parliamentary budget office in Ottawa which suggested that expanding access to Assisted Suicide would lead to nearly 1,200 more such deaths next year – and that this would be a saving of $149 million on end-of-life care spend.

As Life Institute explained in “All about the money?” last year, the attitude can also be found on this side of the Atlantic, pointing to “a disturbing paper published in the journal Clinical Ethics from two Scottish academics argued that Assisted Suicide “would save money and potentially release organs for transplant.”

Marie-Claude Landry, the head of Canada’s Human Rights Commission has warned that euthanasia “cannot be a default for Canada’s failure to fulfill its human rights obligations.

Her comments come in the wake of the “grave concern” expressed last year by U.N. human rights experts, who wrote that Canada’s euthanasia law had a “discriminatory impact” on people with disabilities.

A report by Associated Press this month on the death by euthanasia of Alan Nichols, who did not have a life-threatening disease, seems to add to the growing evidence that this is the case.

Maria Cheng from AP reports:

Alan Nichols had a history of depression and other medical issues, but none were life-threatening. When the 61-year-old Canadian was hospitalized in June 2019 over fears he might be suicidal, he asked his brother to “bust him out” as soon as possible.

Within a month, Nichols submitted a request to be euthanized and he was killed, despite concerns raised by his family and a nurse practitioner. His application for euthanasia listed only one health condition as the reason for his request to die: hearing loss.

Nichols’ family reported the case to police and health authorities, arguing that he lacked the capacity to understand the process and was not suffering unbearably — among the requirements for euthanasia. They say he was not taking needed medication, wasn’t using the cochlear implant that helped him hear, and that hospital staffers improperly helped him request euthanasia.

“Alan was basically put to death,” his brother Gary Nichols said.

Not to be outdone by the Netherlands, Canada is also moving towards legalising assisted suicide for teens and children.

The Canadian experience is a shocking indictment of what state-facilitated suicide very quickly becomes. It is unlikely, however, that those facts will bring Irish politicians looking at the issue to over-ride their desperate need to be seen as driving the best little liberal country in the world.

But for all the virtue signalling and false claims of compassion, a harsh reality should be pointed out.

Legalising assisted suicide is now society’s way of ridding ourselves of the “burden” of the sick, the elderly, those with disabilities, and those who may be sad, depressed, or vulnerable.

It would make for a more honest conversation if, like Ebenezer Scrooge, that motivation was admitted to.

This piece was first published on Gript.

Featured

- Calls for inquiry: 108 babies born alive then die after abortion

- Britain: Assisted Suicide Bill ‘will almost certainly fail’

- Every Life Counts: sending love and care for sick babies

- "A step backwards": Jersey has legalised Assisted Suicide

- 8,000 babies saved by Abortion Pill Reversal

- Spain Moves To Restrict Pro-Life Protests Near Abortion Clinics

- Mediums and abortion: a dangerous narrative

- Man jailed for 9 years for forced abortion

- Abortion coercion has arrived in Ireland – the NWC are silent

- Review of at-home abortions 'needed after coercion case'

- French Govt to remind 29-year-olds of biological clock

- Rally for Life 2025